ART

There is so much to celebrate in Mexico’s rich and beautiful artistic and literary heritage, as well as a thriving contemporary scene, that we can only scratch the surface here, but we hope to inspire you to delve deeper and find out more! Also, take a look at our Events page to find out what the British Mexican Society is planning.

Mexican Muralism

Mexican muralism is the term used to describe the revival of large-scale mural painting in Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s. The three principal artists were José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Rivera is usually considered the chief figure. All three were committed to left-wing ideas in the politically turbulent Mexico of the period and their painting reflects this. Siqueiros in particular pursued an active career in politics, suffering several periods of imprisonment for his activities. Their use of large-scale mural painting in or on public buildings was intended to convey social and political messages to the public. In order to make their work as accessible as possible they all worked in basically realist styles but with distinctively personal differences – for example Orozco has elements of surrealism while Siqueiros is vehemently expressionist.

The movement can be said to begin with the murals by Rivera for the Mexican National Preparatory School and the Ministry of Education, between 1923 and 1928. Orozco and Siqueiros worked with him on the first of these. The Mexican Muralists carried out a number of major works in the USA which helped bring them to wide attention and had some influence on the abstract expressionists.

Notable among these are Rivera’s 1932–3 murals in the Detroit Institute of Arts depicting the Ford automobile plant (extant), and at the Rockefeller Center, New York (destroyed on Rockefeller’s orders after a press scandal when a portrait of Lenin was noticed in the mural); Orozco’s The Epic of American Civilisation at Dartmouth College, New Hampshire and his Prometheus at Pomona College California (both extant); and Siqueiros’s 1932 Tropical America in Los Angeles. Siqueiros’s mural – an attack on American imperialism in Mexico – was painted over some time after it was made, but is now undergoing restoration. (Source: Tate.org.uk)

Here is an interesting overview video of the Mexican Muralists.

Frida Kahlo

A true Mexican talent, who became a global icon and inspiration to millions, Frida Kahlo had a fascinating life – much of it linked closely with fellow artist Diego Rivera. The following is a detailed U.S documentary with plenty of original footage and a valuable insight into Kahlo’s life and work.

Leonora

Carrington

Known as Britain’s lost surrealist, Women’s Lib champion Leonora Carrington was a rebellious Lancashire-born artist who despite being little known in her native UK was an impressive figure on the Mexican art scene. One of the last surviving (and one of the most prolific) contributors to Mexican surrealism before her death in 2011, her artwork was often revolutionary in its exploration of female sexuality. One of her murals can be seen at the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City. (Source: http://www.thecutlturetrip.com)

Featuring rare archive footage, this short film follows Leonora Carrington’s cousin and journalist, Joanna Moorhead, exploring the artist’s story.

(Source: YouTube Tate Channel)

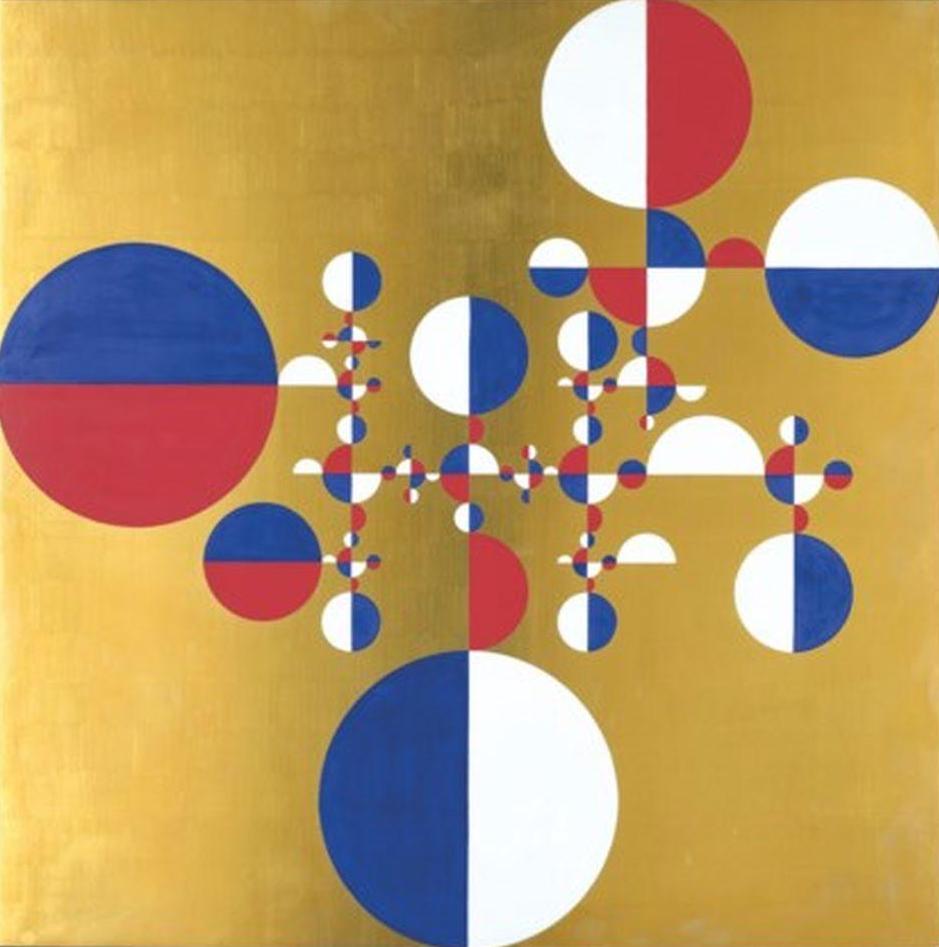

Sebastián

Nulla quis lorem ut libero malesuada feugiat. Curabitur non nulla sit amet nisl tempus convallis quis ac lectus.Like Madonna, Prince and Banksy before him, Mexican sculptor Sebastián goes by just one name. If that doesn’t say iconic, we don’t know what does. Despite his reputation you’ve probably never heard of him, although you will almost certainly have been witness to one of his many sculptures. Situated in various urban locations all over the world, including his native Mexico, Japan, Buenos Aires and Havana, these massive, predominantly steel or concrete and often geometric sculptures are considered unique to both Mexico and Latin America. Easily his most famous piece is Mexico City’s Caballito. (Source: http://www.theculturetrip.com)

Gabriel Orozco

Gabriel Orozco may not be a relation of the aforementioned José Clemente Orozco but he’s an equally iconic, albeit more recent, Mexican artist. Having dabbled in photography, painting, drawing and sculpture in equal measure, you might be forgiven for thinking he’s merely a Jack of all trades, yet you couldn’t be further from the truth. Often referred to as one of this decade’s most influential artists, you can catch his work at the excellent kurimanzutto gallery in Mexico City. (Source: http://www.theculturetrip.com)

LITERATURE

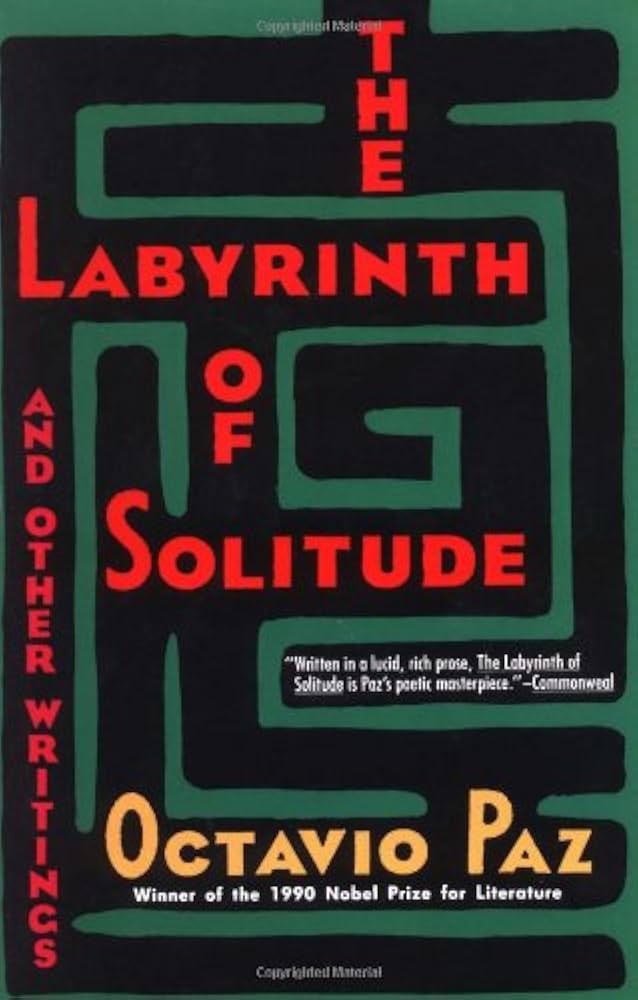

During the second half of 20th century, Mexican literature diversified into themes, styles and genres. There were new groups such as Literatura de la Onda (1960s), which was characterised by an urban, satirical and rebellious style; among the featured authors were Parmenides García Saldaña and José Agustín; La mafia cultural (1960s) was composed of Carlos Fuentes, Salvador Elizondo, José Emilio Pacheco, Carlos Monsivais, Inés Arredondo, Fernando Benítez among others. In 1990, Octavio Paz became the only Mexican to date to have won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Octavio Paz

Born in March 31, 1914 —died April 19, 1998, Mexico City. Paz was a Mexican poet, writer, and diplomat, recognized as one of the major Latin American writers of the 20th century. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990 and received numerous other awards, including the Cervantes Prize.

Paz’s family was ruined financially by the Mexican Civil War, and he grew up in straitened circumstances. Nonetheless, he had access to the excellent library that had been stocked by his grandfather, a politically active liberal intellectual who had himself been a writer. Paz was educated at a Roman Catholic school and at the University of Mexico. He published his first book of poetry, Luna silvestre (“Forest Moon”), in 1933 at age 19. In 1937 the young poet visited Spain, where he identified strongly with the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War. His reflection on that experience, Bajo tu clara sombra y otros poemas (“Beneath Your Clear Shadow and Other Poems”), was published in Spain in 1937 and revealed him as a writer of real promise.

Source: http://www.britannica.com

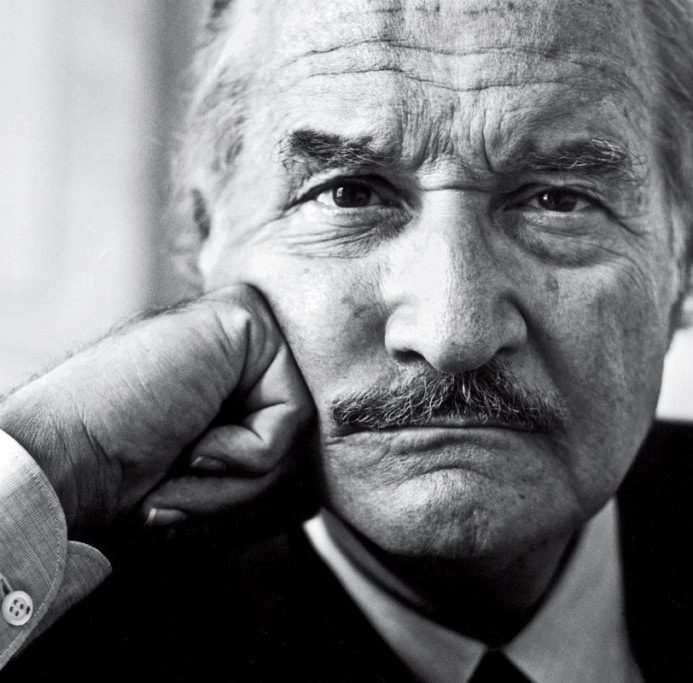

Carlos Fuentes

Born November 11, 1928, Panama City, Panama—died May 15, 2012, Mexico City, Mexico. A Mexican novelist, short-story writer, playwright, critic and diplomat whose experimental novels won him an international literary reputation.

The son of a Mexican career diplomat, Fuentes was born in Panama and traveled extensively with his family in North and South America and in Europe. He learned English at age four in Washington, D.C. As a young man, he studied law at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City and later attended the Institute of Advanced International Studies in Geneva. Fuentes was a member of the Mexican delegation to the International Labour Organization (ILO) in Geneva (1950–52), was in charge of cultural dissemination for the University of Mexico (1955–56), was cultural officer of the ministry (1957–59), and was ambassador to France (1975–77). He also co-founded and edited several periodicals, including Revista Mexicana de literatura (1954–58; “Mexican Review of Literature”).

Source: http://www.britannica.com

The Old Gringo by Carlos Fuentes

Juan Rulfo

Juan Rulfo, in full Juan Nepomuceno Carlos Pérez Rulfo Vizcaíno (born May 16, 1917, Mexico—died January 7, 1986, Mexico City), Mexican writer who is considered one of the finest novelists and short-story creators in 20th-century Latin America, though his production—consisting essentially of two books—was very small. Because of the themes of his fiction, he is often seen as the last of the novelists of the Mexican Revolution. He had enormous impact on those Latin American authors, including Gabriel García Márquez, who practised what has come to be known as magic realism, but he did not theorize about it. Rulfo was an avowed follower of the American novelist William Faulkner.

As a child growing up in the rural countryside, Rulfo witnessed the latter part (1926–29) of the violent Cristero rebellion in western Mexico. His family of prosperous landowners lost a considerable fortune. When they moved to Mexico City, Rulfo worked for a rubber company and as a film scriptwriter. Many of the short stories that were later published in El llano en llamas (1953; The Burning Plain) first appeared in the review Pan; they depict the violence of the rural environment and the moral stagnation of its people. In them Rulfo first used narrative techniques that later would be incorporated into the Latin American new novel, such as the use of stream of consciousness, flashbacks, and shifting points of view. Pedro Páramo (1955; Eng. trans. Pedro Páramo) examines the physical and moral disintegration of a laconic cacique (boss) and is set in a mythical hell on earth inhabited by the dead, who are haunted by their past transgressions.

Source: http://www.britannica.com

Laura Esquivel

Born on September 30, 1950, in Mexico City, Mexico. Esquivel began writing while working as a kindergarten teacher. She wrote plays for her students and then went on to write children’s television programs during the 1970s and 1980s.

Esquivel often explores the relationship between men and women in Mexico in her work. She is best known for Como Agua para Chocolate (Like Water for Chocolate), an imaginative and compelling combination of novel and cookbook. After the release of the film version in 1992, Like Water for Chocolate became internationally known and loved. The book has sold more than 4.5 million copies.

Esquivel has continued to show her creative flair and lyrical style in her later work. Accompanied by a collection of music, her second novel The Law of Love (1996) combined romance and science fiction. Between the Fires (2000) featured essays on life, love, and food. Her novel, Malinche (2006), explores the life of a near mythic figure in Mexican history, the woman who served as Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés’s interpreter and mistress.

More recently, Esquivel has entered politics, winning a seat in Mexico City’s Local Council.

Like Water for Chocolate by Laura Esquivel

Source: http://www.biography.com